10 Extremely Long Movies You Must Watch at Least Once

Some films demand more from their audience — not just attention but time. In an era of social media, TikTok videos, and ever-diminishing attention spans, it can be hard to focus on a movie for two, three, or even four hours. Still, some films are great enough to justify their extended runtimes, leaving a much bigger impact than they would in any other form.

With this in mind, this list looks at some of the must-watch movies that clock in at three hours or more. They range from dramas to slice-of-life stories and even comedies. Whether you’re watching the passage of time over three decades, a trial that unpacks the soul of a nation, or the slow unraveling of a housewife’s psyche, these films ask you to sit, wait, and see, rewarding viewers who stick with them.

10

‘Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles’ (1975)

Directed by Chantal Akerman

“It’s Tuesday. So I peel potatoes.” This three-hour-plus opus topped Sight & Sound’s 2022 poll of the greatest movies of all time, and not without reason. Jeanne Dielman is a radical act of slow cinema that turns the mundane into something quietly monumental. For most of its runtime, the film simply follows Jeanne (Delphine Seyrig), a widowed mother living in Brussels, as she performs her daily domestic rituals — cooking, cleaning, shopping, and occasionally hosting male clients for sex work.

Nothing appears to happen, but in that nothingness, something seismic simmers. Scenes unfold in real-time, and Jeanne often moves in and out of frame, her presence felt even in absence. The camera documents her life with ceaseless attention, noticing every detail, every repetition. Along the way, the movie quietly dismantles conventions of narrative, genre, and time. Then, in the third act, everything explodes: a worthy, devastating payoff for all the buildup.

9

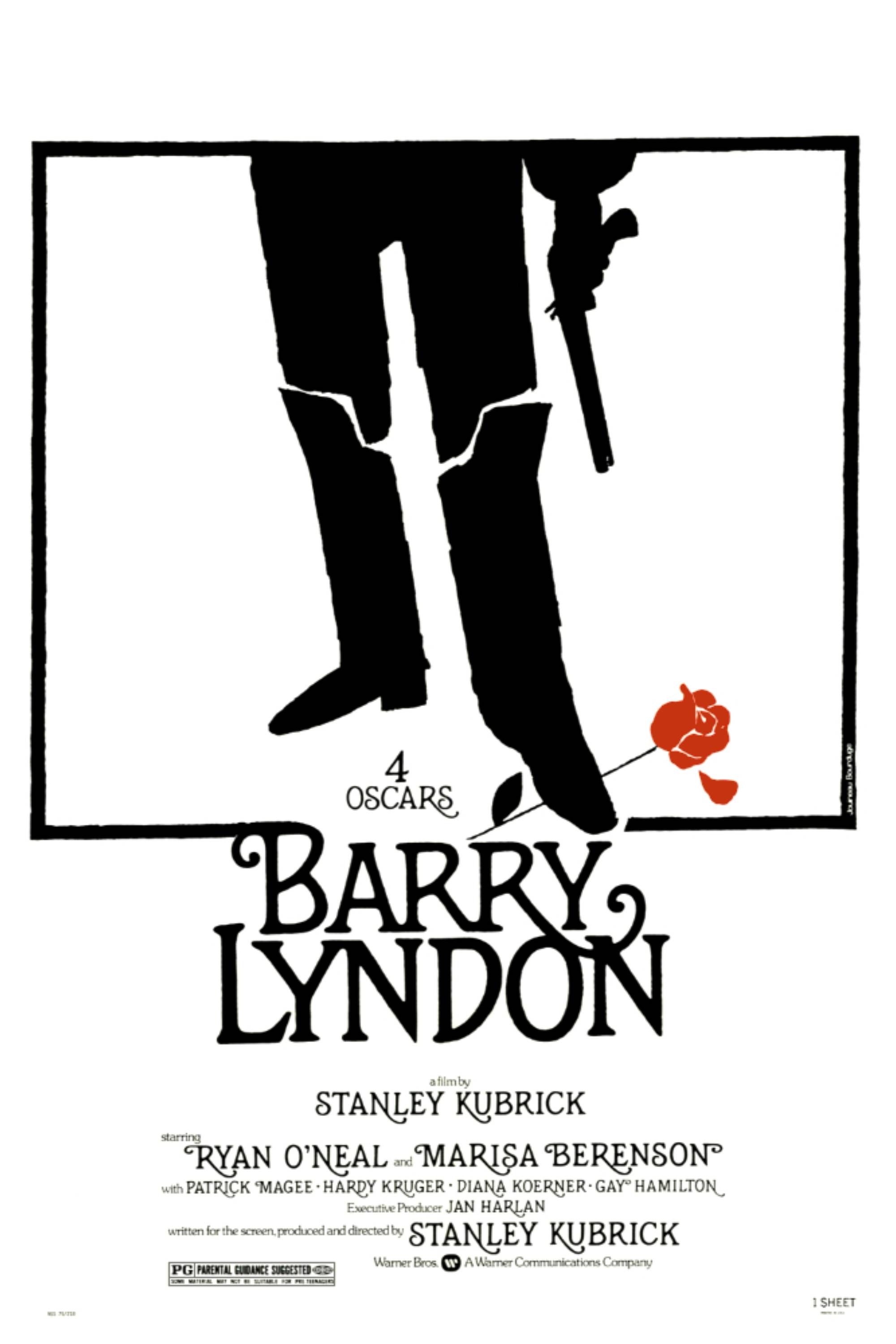

‘Barry Lyndon’ (1975)

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

“It is an unfortunate fact that we can seldom enjoy a story the first time we hear it.” Set in the 18th century, Barry Lyndon follows Redmond Barry (Ryan O’Neal), a penniless Irishman who rises through the social ranks from romantic dreamer to jaded aristocrat. Barry fights duels, cons nobility, and marries into wealth, but his ascent is mirrored by a slow moral disintegration. Kubrick captures it all with long takes and natural lighting, making for one of his most unique projects.

Barry Lyndon is the director at perhaps his least accessible, but he compensates for the lack of overt entertainment value with emotional complexity and a bevy of then-cutting-edge techniques, particularly in terms of the cinematography. For example, they used three super-fast 50mm lenses that had been developed for NASA. Although not embraced on release, Barry Lyndon‘s critical estimation has improved a lot over the decades, with it landing fairly high on Sight & Sound’s 2022 poll of the greatest films ever made.

8

‘Fanny and Alexander’ (1982)

Directed by Ingmar Bergman

“I believe the world is an evil place. But I’ve reconciled myself to God’s indifference.” Fanny and Alexander is one of the most personal films by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, who also made the legendary Wild Strawberries and The Seventh Seal. It begins in the warm, eccentric Ekdahl household. But when Alexander’s (Bertil Guve) father dies and his mother remarries a severe bishop, the tone curdles, and the film slowly transitions from vibrant family drama to gothic captivity tale.

The movie clocks in at 188 minutes in the original theatrical release and a whopping 312 minutes in the TV miniseries form, which has since also been screened in cinemas. While this length is understandably daunting, Fanny and Alexander rewards viewers with a layered meditation on childhood informed by the filmmaker’s life. Not for nothing, Bong Joon-ho has said that the movie has “the most beautiful ending to a feature film career in the history of cinema.”

7

‘Gone with the Wind’ (1939)

Directed by Victor Fleming

“Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” At nearly four hours long, Gone with the Wind is the ultimate Classic Hollywood epic. Set during the American Civil War and its aftermath, it centers on Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh), a fiercely determined Southern belle whose vanity, ambition, and survival instinct drive her through a world collapsing around her. She loves Ashley (Leslie Howard), marries Rhett (Clark Gable), loses everything, and claws it all back again, often at great personal cost.

The movie was a cultural juggernaut on release, sweeping the awards season and dominating the box office. While the visuals — burning Atlanta, flowing gowns, and wind-swept plantations — remain iconic, Gone with the Wind‘s romanticized portrayal of the antebellum South has come under scrutiny in recent times. Nevertheless, the sweeping narrative remains immersive, and the performances are still great, including the towering, dignified turn by Hattie McDaniel. The performance earned her the Best Supporting Actress Oscar, making her the first Black person to win an Academy Award.

6

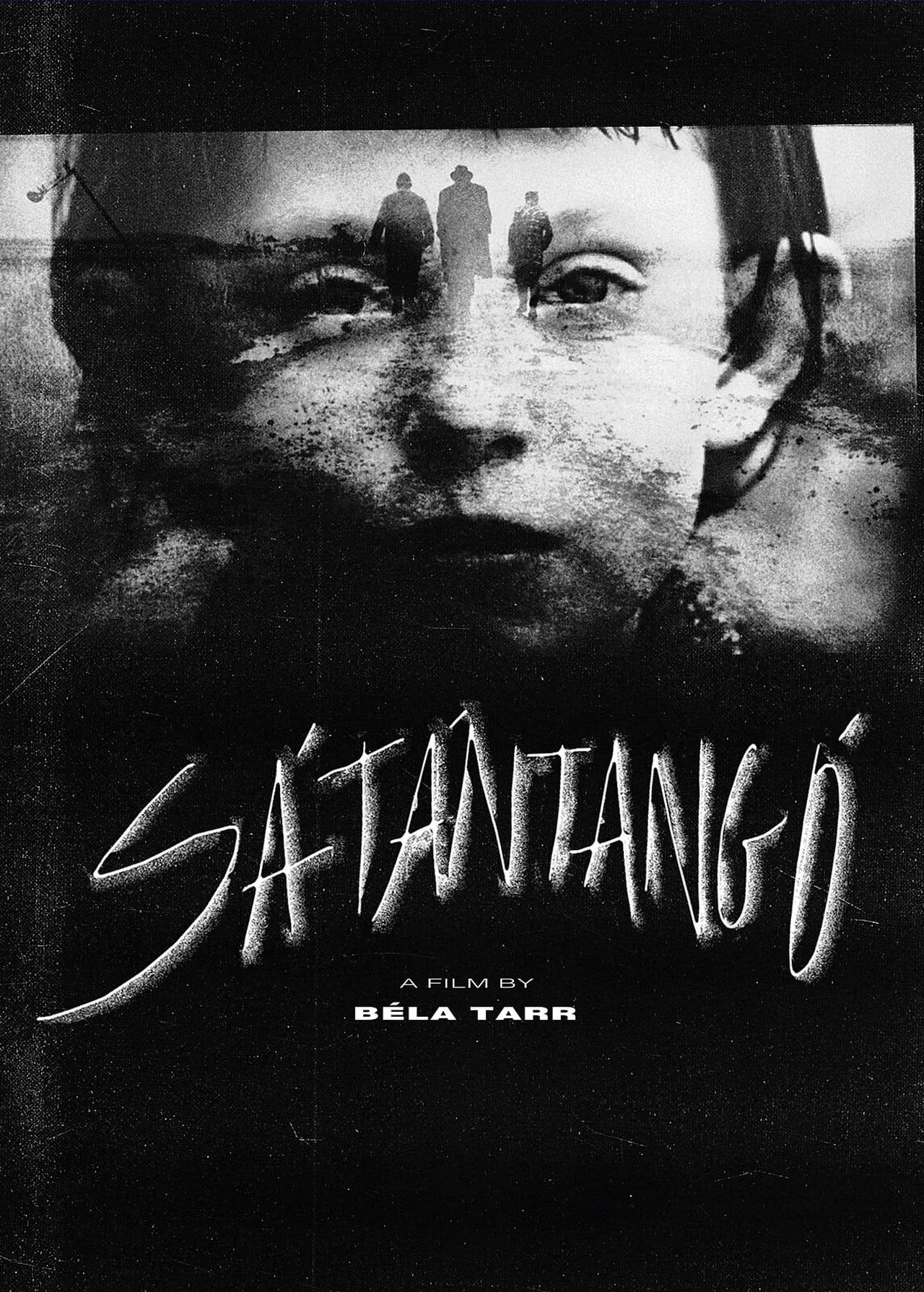

‘Sátántangó’ (1994)

Directed by Béla Tarr

“We’ll go on forever, endlessly, toward our doom.” At seven and a half hours, Béla Tarr‘s Sátántangó isn’t a movie so much as an act of endurance. Set in a bleak, rain-soaked Hungarian village after the collapse of a collective farm, it tracks a group of aimless, disillusioned residents who await the return of Irimiás, a figure who may be a messiah or a manipulator — or both. There’s no conventional plot; instead, Tarr crafts a doomy, gloomy world defined by decay and inertia.

The camera moves at a glacial pace as well, often holding a single shot for ten minutes or more. These takes are skillful, serving to build tension. Many viewers will find Sátántangó‘s grim tone off-putting, which is understandable, but there is genuine thoughtfulness amidst the darkness. Tarr specialized in this kind of pessimistic, philosophical storytelling (one of his movies is literally called Damnation), and, here, his nihilistic vision is at its most striking.

5

‘Lawrence of Arabia’ (1962)

Directed by David Lean

“The trick, William Potter, is not minding that it hurts.” No list of cinematic epics would be complete without Lawrence of Arabia. Sprawling across deserts and decades, David Lean‘s behemoth features Peter O’Toole as T.E. Lawrence, the eccentric British officer who becomes a reluctant revolutionary during World War I, leading Arab tribes in rebellion against the Ottoman Empire. Lawrence is brave, brilliant, and deeply fractured, and the film rides that contradiction all the way to the horizon.

Lawrence of Arabia remains impressive, not just because it’s a technical marvel but because it’s such a good character study, not just empty spectacle; there’s emotion alongside the grand set pieces. O’Toole’s performance more than rises to the occasion. The cinematography and editing also match the grandeur of the story. From the moment Lawrence extinguishes a match and the film cuts to the blazing expanse of the desert, you know you’re watching a master at work.

4

‘Once Upon a Time in America’ (1984)

Directed by Sergio Leone

“I like the stink of the streets. It cleans out my nostrils.” Sergio Leone‘s final film, Once Upon a Time in America covers nearly fifty years in the life of Jewish gangster David “Noodles” Aaronson (Robert De Niro). The narrative drifts through three time periods—childhood in 1920s New York, the peak of Prohibition-era power in the 1930s, and a strange, mournful coda in the 1960s.

It’s one of De Niro’s most restrained performances. He plays Noodles as a man perpetually retreating from the past he helped create. He has complicated relationships, particularly with James Woods‘ volatile Max and with Deborah (Elizabeth McGovern), the woman he adores and ruins, which carry the weight of myth and melancholy. The movie is definitely bloated and would have benefited from some more judicious editing, but there’s no denying its strengths. The final piece of the puzzle is the score by Ennio Morricone, which is lush and mournful, ranking among the legend’s very best work.

3

‘Judgment at Nuremberg’ (1961)

Directed by Stanley Kramer

“This is what we stand for: justice, truth, and the value of a single human being.” This towering legal drama from director Stanley Kramer (On the Beach, Who’s Coming to Dinner) depicts the 1947 trials of Nazi judges and prosecutors held accountable for crimes committed under Hitler’s regime. Spencer Tracy leads the cast as Judge Dan Haywood, tasked with sifting through layers of guilt, ideology, and moral compromise.

The cast is formidable — Maximilian Schell won an Oscar as the passionate defense attorney, and Judy Garland and Montgomery Clift both deliver haunting cameos as victims of Nazi policies. Burt Lancaster plays one of the most chilling figures: a silent, stoic defendant whose final confession makes for a standout moment. On the writing side, Abby Mann‘s Oscar-winning script strikes a potent balance between rhetoric and emotion. With its moral complexity and powerful courtroom framework, Judgment at Nuremberg probes some of the thorniest ethical questions raised by this dark chapter in human history.

2

‘Seven Samurai’ (1954)

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

“This is the nature of war: by protecting others, you save yourself. If you only think of yourself, you’ll only destroy yourself.” Seven Samurai centers on a desperate farming village that hires seven masterless samurai to defend them from bandits. What sounds like a simple setup evolves into a rich exploration of honor, class, leadership, and the costs of violence. Each of the seven is distinct, from the stoic leader Kambei (Takashi Shimura) to Toshiro Mifune‘s wild, scene-stealing Kikuchiyo. Their bond with the villagers forms the heart of the movie.

Seven Samurai fires on all cylinders, succeeding as a rousing action epic, a poignant human drama, a meditation on class and sacrifice, and a precise period piece. Few movies combine excitement and depth so deftly. Seven Samurai went on to be hugely influential; countless remakes followed, and many of its elements became cinematic staples, not least its central “assembling the team” plot device.

1

‘The Godfather Part II’ (1974)

Directed by Francis Ford Coppola

“Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer.” As both sequel and prequel, The Godfather Part II expands the world of the Corleone family in two directions: forward, with Michael Corleone (Al Pacino) consolidating power and descending into moral ruin, and backward, with young Vito Corleone (Robert De Niro) rising from immigrant obscurity to mafia patriarch. The result is a nearly three-and-a-half-hour saga that’s more operatic, more ambitious, and arguably more tragic than its predecessor.

The Godfather Part II is the archetypal mobster movie, but it also transcends gangster genre expectations: it isn’t just about the violence inflicted by men, but the emotional devastation they leave behind. The character development is rich and layered, particularly as Pacino’s performance grows colder and quieter. Through Michael and Vito, Francis Ford Coppola makes a broader statement on a nation seduced by its mythologies. The intervening decades have not diluted this movie’s power; it’s still a masterpiece.

.jpg)