Jewish Refugee Museum, Shanghai | The Official Schoolgirl Milky Crisis Blog

There is a poem on the wall of Shanghai’s Jewish Refugee Museum that stopped me in my tracks. It was written by Dan Pagis (1930-1986).

In the last room in our house

At the edge of a wondrously curled cloud

A Chinese rider raced by on his horse

Out of breath – embroidered in silk.

And now, when I no longer know whether

He dissolved in the cloud or burned down with the house

I realise we were both wrong and that

We were one, each embroidered on the other.

Shanghai comes into its own when it is directly involved in the story being told. Which is why I urge visitors not to go in search of the all-China generic galleries to be found at the massive museum in the city centre, but to look for those places where Shanghai celebrates itself. There is, for example, the charming Shanghai City Museum, which remains the only real reason to visit the Oriental Pearl Tower in Pudong. Readers of this blog will already be aware of my enthusiasm for the Longhua Martyrs Cemetery, which enumerates the many Party-approved heroes and heroines who fought to make Shanghai what it is today.

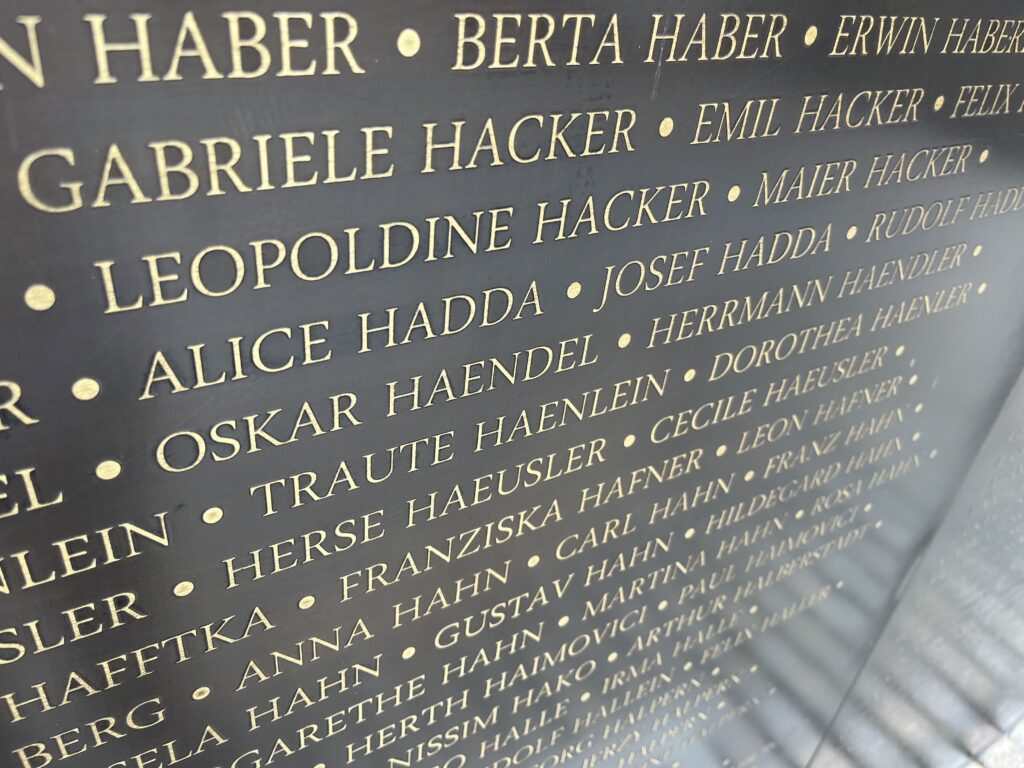

Shanghai’s Jewish Refugee Museum is another fascinating place, a monument to a phenomenon that supposedly came and went long, long ago. It is a surprisingly lavish venue chronicling the lives of 13,732 exiles from Nazi Germany as they tried to make the best of life in Shanghai, one of the few places in the world that offered them sanctuary.

Pictures are not permitted in the museum interior, possibly as a result of the same trepidation that requires all visitors to leave their cigarette lighters at the entrance. But the story told inside, like that in the Martyrs Cemetery, manages the difficult task of taking a tale of misery and misfortune, and reframing it as a celebration and commemoration. There is some treatment of the Jews already present in the International Settlement, where, as regular readers will already know, a thriving community of Russian émigrés tried to make do and mend after fleeing the 1917 Revolution. But the museum’s primary interest is in the years between 1938, when the first Jewish refugees arrived from Germany, and 1956, the year in which the last of them disembarked for new lives in Australia, Canada and multiple other places.

In a diverse mix of dioramas, video footage and exhibits, the museum tells the tale of the sudden ferment of Jewish and European friendships, feuds and families, the new careers and businesses that sprang up to serve this sudden influx of newcomers, and the long, long tail of their associations and connections. Permitted visa-free entry to Shanghai after most other places around the world had refused them access, the Jews soon had to contend with the city’s Occupation by the Japanese, which led to the creation of the Shanghai Ghetto in 1943. The end of the war in 1945 soon pivoted into a Civil War between the Communists and Nationalist Chinese, while the last of the Jews scrambled to find safe passage to another country.

A sign at the door exhorts anyone with family connections to Shanghai’s Jews to make themselves known to the curators – and clearly there have been several cases where visitors have become exhibits, captured on film discussing their grandmother’s wedding dress or the day they ran the gauntlet of Japanese military police.

Sometimes, one gets a sense of real happiness in a museum. It is very rare, but every now and then, the narrative on display becomes a descant of jubilation – I have felt it before only rarely, most memorably at the Norway’s Resistance Museum in Oslo. The Jewish Refugee Museum veritably beams with pride at the way that materialist, money-grubbing Shanghai suddenly flung open its doors to a foreign people in need, and at the many hundreds of strangers who come to its doors eight decades later, to announce that their ancestors still speak fondly not only of violin concertos on the Roy Roof Garden and pastrami at Horn’s Snack Bar, but also of the way that China became so intimately and briefly part of their lives, leaving them each embroidered on the other.

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of China.